Experiencing the Japanese Spirit in the Sierra Madre Mountains

words and photos by Desmond Catolos

There’s one thing that has become a ritual every time I come to visit Sitio Magata, a remote community of indigenous people in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Rizal. It’s to stop by the Aklatan or the Sierra Madre Library-2.

Founded by Mr. Yanai, Mr. and Mrs. Hariyama, and Mr. and Mrs. Kaneko in the late 1990’s, the library has since been a place for anyone eager for learning and enjoyment in the community. Of course, you may be new to this village, in which case the names Yanai and Kaneko may not be familiar to you, but mention it to anyone who has lived here and you will learn that Yanai and Kaneko were unquestionably amongst the village’s most respected regular visitors. This endeavor was realized together with Japan Overseas Education Support Federation (JOES), a non-profit organization that funds literacy and education projects in areas of need that supported the mission of the Kanekos and the other Japanese volunteers. Situated on top of a hill that looks down on the pristine Limutan River and surrounded by a well kept garden of native floras, the three-room structure is an undeniable landmark of the village.

As I slipped off my slippers outside the door (as everybody does) and upon entering the room barefoot, one tends to be struck by the contrast between the bookcases and tables, lit by warm low light coming from the translucent roof, and the rest of the room, which was in shadow. Sunlight, no matter what time of the day, illuminated the area around the center of the room. Surrounded on all sides by bookcases, it gave me a certain feeling of warmth, of repose, a sense of homeliness. Then I quickly noticed the isolated groups of children scattered all about the room. The children were talking with each other, they took turns sharing the contents of the books they found interesting as they flipped through the pages, happy and content.

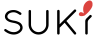

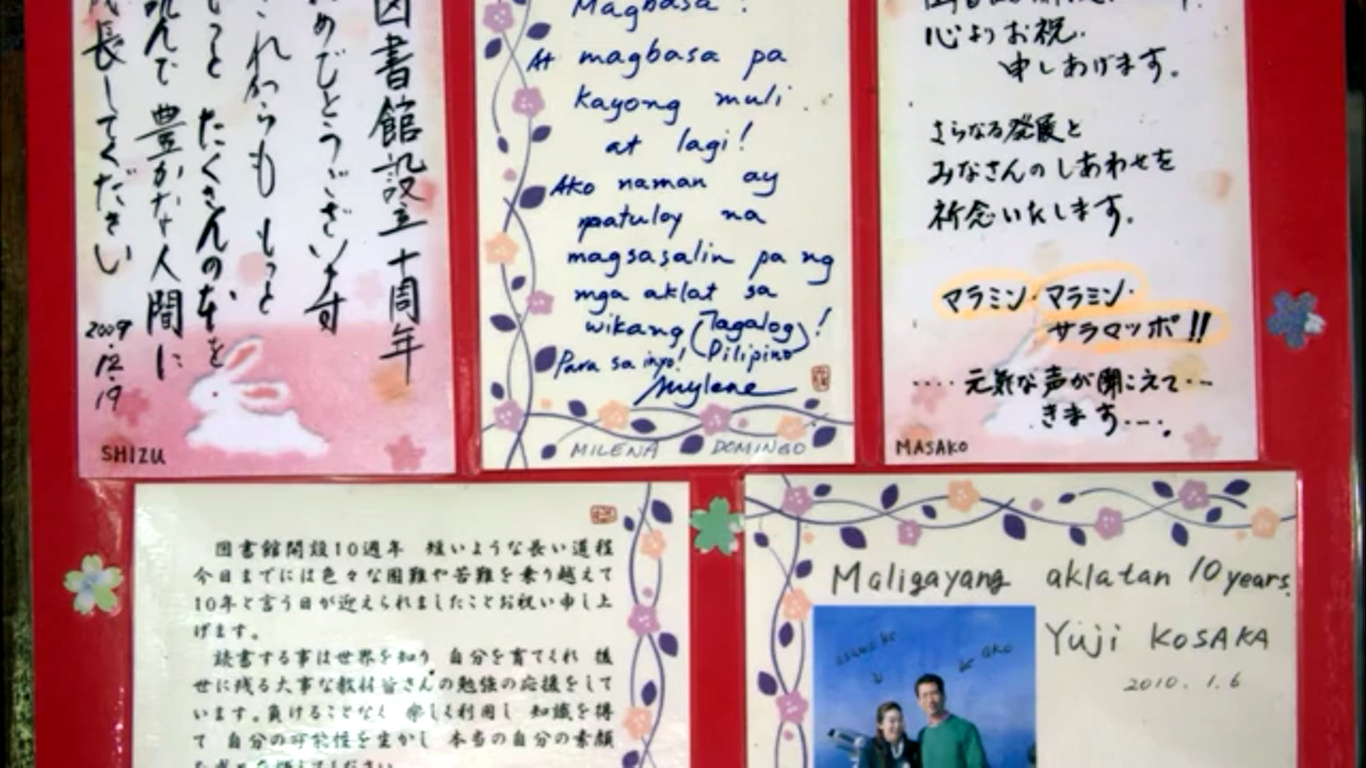

Here, I came to know a young lady librarian, Janice Embile, who also happens to be one of the translators of the books donated by the Japanese that were originally published in Nihongo. She was briefly trained in Japan courtesy of JOES to learn the language. Driven by the honor bestowed on her more than anything else, she tirelessly and meticulously translates the books from Nihongo to Tagalog to the best of her abilities. A small table dedicated to her work occupied one corner of the room just beside an open window with piles of books neatly arranged. As I watched her work, I began to see what the library meant for her. It’s for her own people after all. Janice worked with skill and confidence as she visualized the language from Nihongo then to Tagalog. Sensing my presence, she looked up from her books and greeted me affably. Janice simply asked the children to settle and to keep their voices to a minimum. The children stared at me for a few seconds then back down at the books again. All the while, they continued to mutter lines of dialogue under their breath as they read on, fully absorbed. One little girl attracted the attention of Janice. She pointed to a volume of books on top of a shelf that was too high for her to reach. Janice stood up from her table, took the book down from the shelf and handed it to the little girl to her obvious delight. As I continued to scan the interior, I noticed posted on the wall were photos of the Japanese who visited Magata and the library.

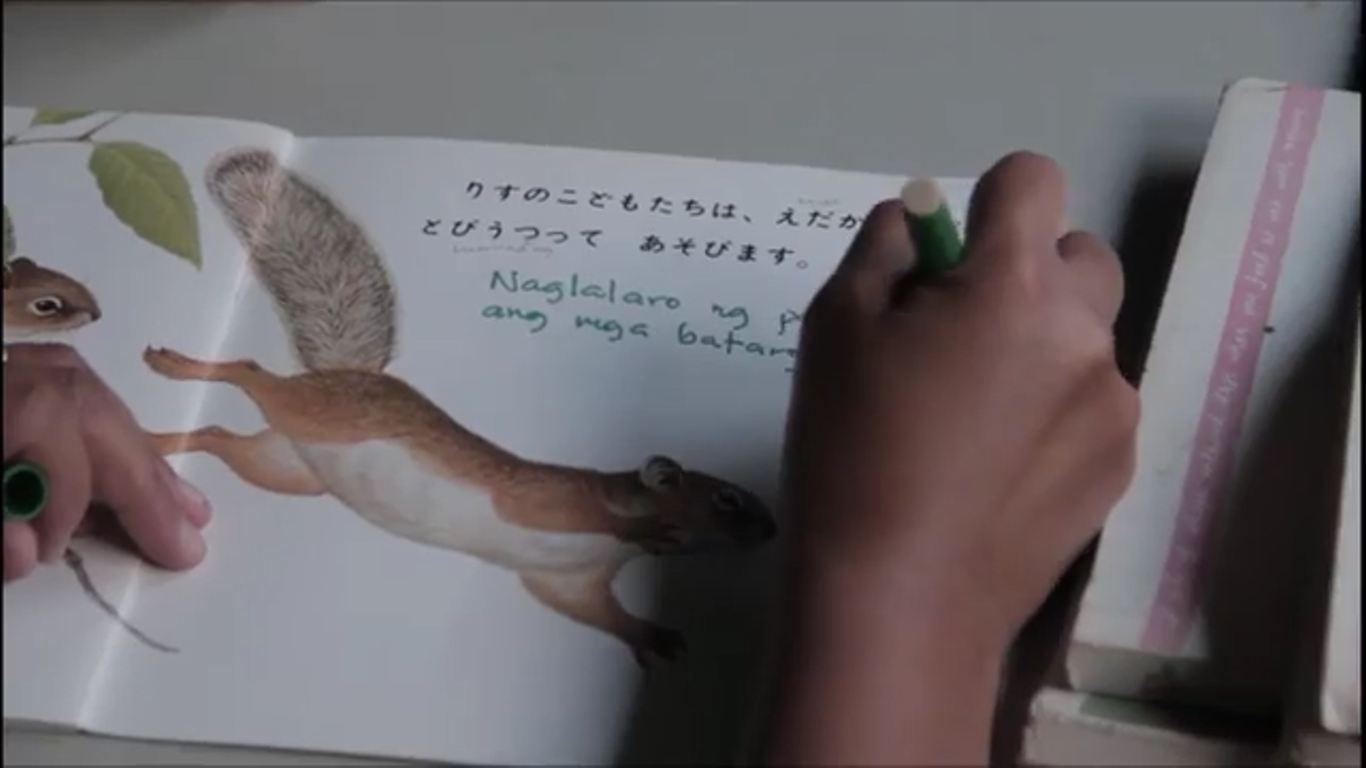

Curious, I took out some books from the shelf. The books were in good condition, pleasant to smell. As I leafed through the pages till I reached the back cover, I discovered that the donors were mostly Japanese children, which I presume were from the ages seven to perhaps their teenage years. The books were their personal possessions and after they finished reading them, they donated the books here, to their Filipino counterparts. Most of the books were accompanied by photos of the donors with handwritten words like “kamusta kayo” and other formal Tagalog greetings inscribed by the donors themselves. It was something special.

With no direct access to electricity and the internet and with the pandemic making it impossible to attend regular school, the books became treasured possessions of the children in the area.

I visit Sitio Magata every few months to quietly pass the time, and I must say I don’t think I ever missed a day going to the library. Even if you walk the same road a hundred times, you’ll find something different each time. I have never been to Japan but somehow, I felt fortunate to experience a piece of the Japanese spirit firsthand through this library. Here is a place no visitor can fail to be moved by. Many times I find myself all alone in the library in silence, so complete one can hear the hum of the river a hundred meters away. But today, the children are noisy and happy. Outside, the song of birds and cicadas fill the air.

Editor’s Note:

A library is a sign of social progress when we prioritize education.

A heartfelt essay situated not far from the metro, one can reflect on the situation of communities throughout the country. Janice-san, who has poured her labor of love into Aklatan, cannot do this task alone. But it was made possible thanks to the generosity of the Japanese people and the community.

May we be reminded that like the Japanese founders of Aklatan, we too can serve as a catalyst of hope in our own communities. Through goodwill, they gave the children the added opportunity to learn, with the optimism that they carry those lessons with them as they get older. Long-term impacts may be difficult to measure, but I believe spaces like libraries provide every learner a fighting chance to thrive in life.

It’s still true what they say, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

And sometimes, it takes international cooperation to help the village to raise a child.

– Carlos Ortiz, JFM Program Coordinator for Japanese Studies and Global Partnerships