This is cinematic: some two days before Manila and the entire Luzon closed, I was in a meeting to decide with other film critics the fate of proposals for short film production. Holed up in an old hotel, facing the sea, there were no talks of the virus. It was on the last day of our meeting that I arrived in another hotel to find out that one of the program coordinators had left. With her assistant, she booked a quick return flight home. What triggered that decision was the news – a rumor – then that airports would soon be closing. The next rumor was the lockdown of Manila.

On the 12th of March, I left my apartment in Quezon City, uncertain of what will happen and unbelieving of what will take place in a lockdown. Quarantine as we understood it then was only understood in terms of health and limited to hospitals. No one ever thought of the day when the entire barangay could be quarantined. As what happened, the biggest island of this island-republic was placed on a massive lockdown.

A few weeks before all this, the 12th edition of the Cinema Rehiyon, was just held in Naga City from Feb. 24 to 28. We were hearing already about Covid-19 that time. With Max Tessier, the Manila-based French film critic and scholar, I was worried in particular about the film festival in Udine set in a few months. Already, at the time of our conversation, Northern Italy was darkened by surges in cases and deaths. My article on Eddie Garcia whose films would be exhibited as a tribute to the late actor, was going to be featured in that film fest and I was editing it. Eventually, the festival, which focuses on Asian films, had to be postponed for next year.

By the time I arrived in Naga, the city was almost a ghost town. Curfews were set. I myself went on a self-quarantine in the same hotel where we were billeted during the last gathering of regional filmmakers from all over the land.

It took a long time for the idea of isolation to sink in. It was when I got home, and was handed a towel so I could bathe before I stepped into our home that I knew a new lifestyle is set for all of us. It was the beginning of a new world order.

Ars longa, vita brevis. Art is long, life is short. The ancient aphorism is assuring. Art persists.

While doctors and other health warriors were dying, and debates on the government program on the pandemic were gripping, it seems, the entire nation, cultural workers and filmmakers were looking into something else.

How do we get in touch with each other?

I was worried about the year-long program I crafted for a nationwide film criticism workshop. It was already slated for Bacolod with Tanya Lopez working on it. The Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) has graciously approved the funding. But travel was on hold. Islands and cities would not allow teachers prospective participants to travel.

It was frustrating, annoying to say the least. We were all looking back because no one ever predicted this to happen, no one foresaw days of enforced desolation.

Still, art indeed persists. Technology helps.

By April, there were two names circulating among us: “Zoom” and “Google Meet.” The video-calling interface was becoming the hot issue. Does it work? What benefits shall it bring?

The month of May came without the fiestas. Applications for virtual meetings supplanted face-to-face interaction. On many occasions, there was no choice: we had to meet virtually.

The world started to turn online.

As days went on, it was not anymore the question of anyone knowing Zoom or Google Meet, but the curiosity about what one used.

My schedule began to look normal. Not neo-normal but “normal busy.” Matters postponed were being revived or looked into again. It felt good to think that we still could do what we were doing before the pandemic.

The meetings that were abruptly stopped surged again. We went back to the drawing board or resumed what we were doing. Conferences assumed a new atmosphere. There was distance in the communication but there was also a new form of intimacy. We could see each other. People need not travel. We could meet proponents online. When the visual connection faltered, we continued the meeting through chat rooms.

The Internet, which is the invention created to enable human societies to continue seeing and talking with each other in the event of a nuclear holocaust is now the same technology linking up people and their advocacy of art forms. There are critiques of this present condition. One is that the virtual meeting cannot replace the old form of people being together in one material space. Articles talk of how we are not engineered to be looking at a small screen and not being able to see the nuances of behavior of other people as we talk. Are they all looking at me? Are they interested?

Artifice abounds in these online interactions. We dress up although when we connect with others we are in the confines of our homes, or inside our bedrooms. Or, we do not dress up at all, which gives the meeting an unwanted informality or lack of seriousness.

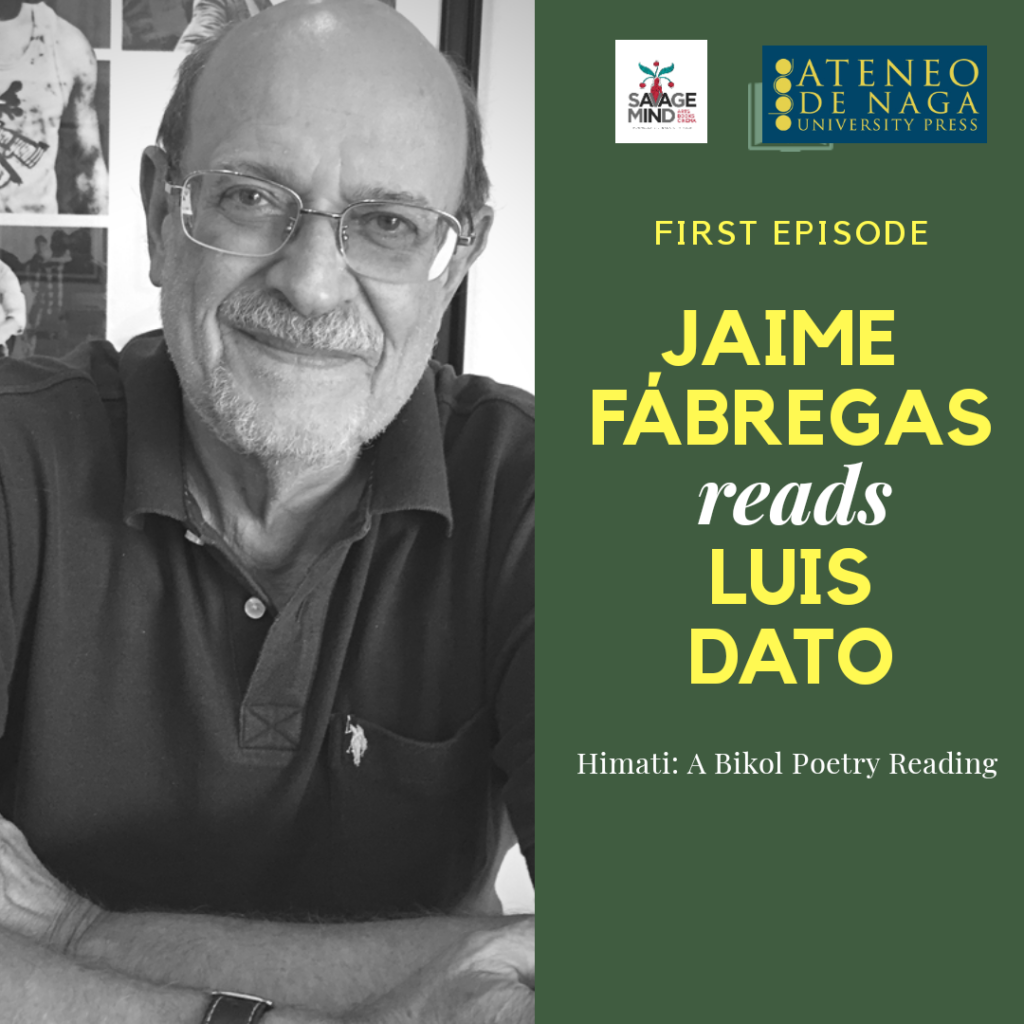

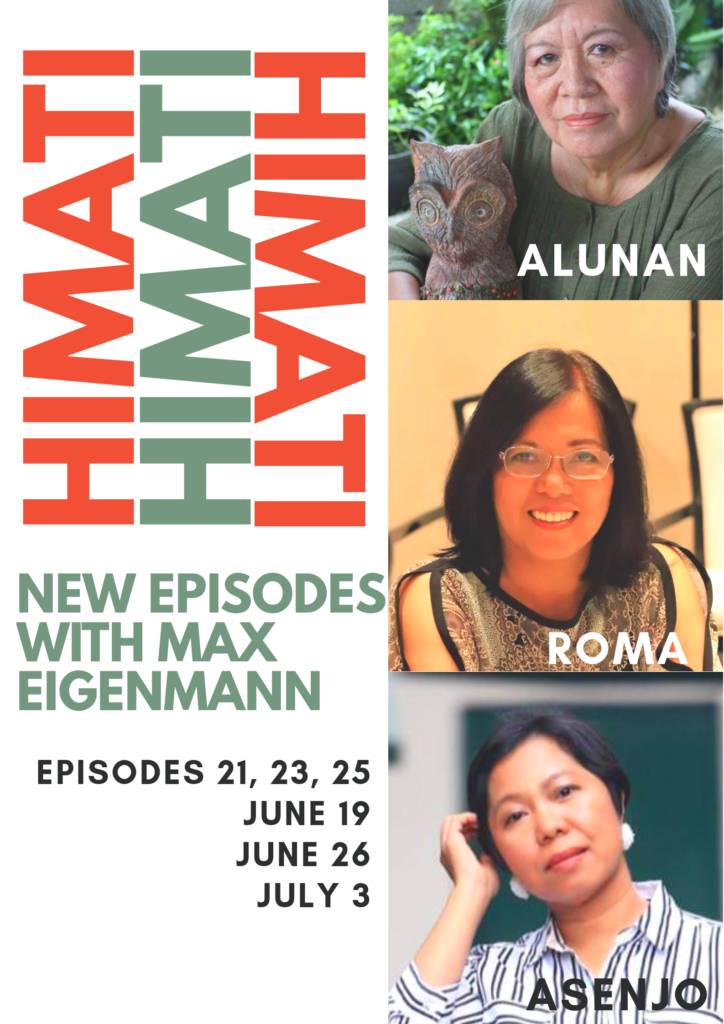

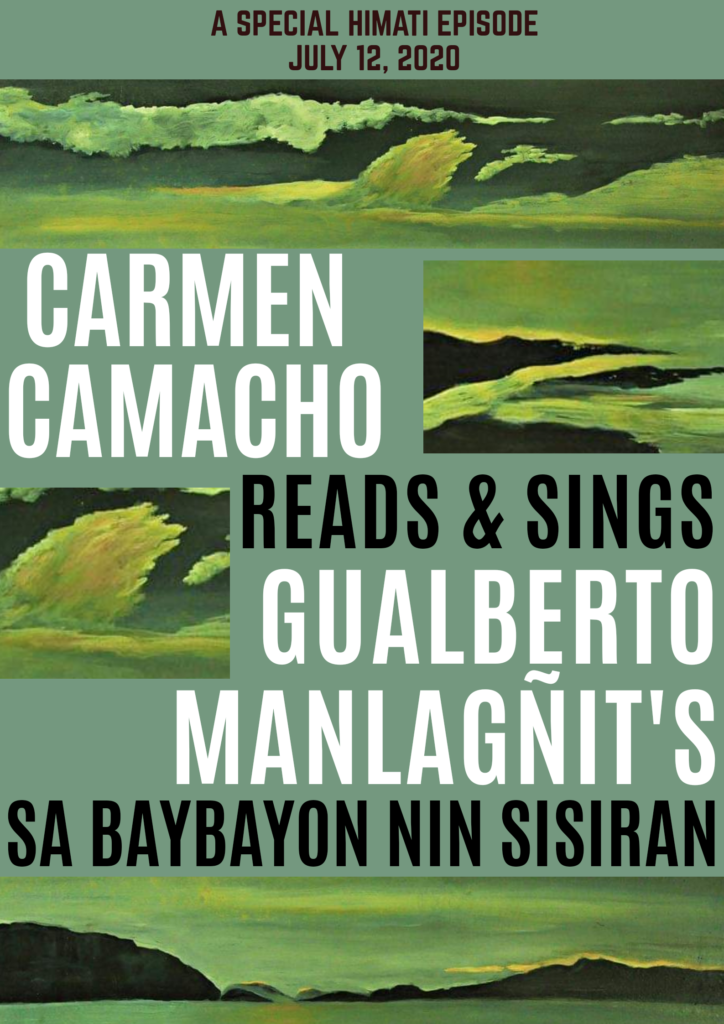

But I cannot complain. At present, I am engaged in major activities all done online. There is the Himati Bikol Poetry Project with Kristian Sendon Cordero of Savage Mind and the Ateneo de Naga University Press. The event began with the celebration of the Literature Week. With all of us in quarantine, we thought of providing a platform for actors and poets to engage the world with poetry. It began with Bikol poets and Bikol readers but soon we requested actors to read for us. Their managers agreed and the actors rendered their artistic services for free. The lockdown became an opportunity for these actors who would, in other times, be so busy that they would not have time for an unusual project like Himati. The reading became a success and until now continues. The online platform, with its name connoting deep listening is more significant given the use of the technology that indeed enables people to listen. It is also so economical that, as I write this, an Argentine actor, Angelo Mutti Spinetta and Filipino actor, Christian Bables, are reading Jorge Luis Borges in Spanish and Filipino, respectively. Angelo was in Argentina recording the original while Christian was somewhere in Quezon City when he interpreted those moving lines.

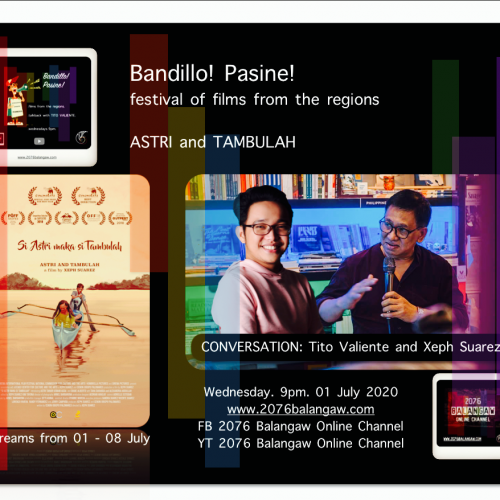

The other activity that I do in this lockdown is with a filmmaker, Jay Altarejos. He formed a Balangaw (meaning Rainbow) Channel for his cultural advocacies. The space given to me is as a critic in conversation with a filmmaker each week. Our program begins with Jay contacting a filmmaker and seeking his permission not only to appear as a guest to talk about his films and arts but also to allow us to screen his film, usually a short film. Again, with the technology we are able to enlist filmmakers from as far as the Visayas and Mindanao. Technology democratizes the distance and empowers a small Manila-based project to empower the independent filmmakers from the peripheries.

A grants program for films demonstrating a Filipino value system was one of the programs under the National Commission for Culture and the Arts. This project managed by filmmaker Elvert Bañares got stalled, like any of the other projects because of the virus. It is presently being continued with our appraisals, evaluations and other discussions done online.

In the middle of the pandemic, an online magazine was born. It is called Bicol Bloc. I was honored to join this new endeavor of Noel De Luna, the Publisher & Chairman Editorial Board, as an editor of Life Section, which was expanded to cover History, Culture and Arts. Editorial meetings are done online. This added to my engagement with Business Mirror, a national broadsheet, where I had always conducted my business online even before the onset of the COVID-19.

After long discussions, our very own group, the Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino, or the Filipino Film Critics, has decided we will push through with the film awards, Gawad Urian. If the artists persist, so, too, the critics. We have already finished the early deliberations online. We will soon begin the shortlisting also online, and then the nominations.

It has been said that this generation is the most connected in terms of technology but the most separated by human and humane interaction. Before the world acknowledged the deadly impact of the virus, there has been consensus that human groups are losing that, which separates them from other animals – language. That language refers to the spoken and written one; it is a medium built on persons looking at the other persons, responding to the cues that we have learned by instinct and by collective experience. That language made hyper and articulated can be transferred to other artistic domains, like plays and cinema. The physical and/or social distancing generated by fear of contagion, however, is now the same factor that is uniting individuals of similar persuasion but separated by spaces.

Ask any artist – actor, dancer, musician, filmmaker, critic, cultural worker – what he or she needs right now. Not the threat of contamination but a new way of looking at the world of arts. The arts movement of the moment, including its practitioners, are asking us to change our perspectives and view performances as a process and product that should continue to be seen online or in whatever form enabled by extrasomatic devices. Mediated by technologies, these arts and their requirements are not limited to the enabling of more efficient Internet connection. There is the need for support from institutions of arts that have evolved differently from those that are live on stage with live audiences to these forms that are produced live online but are also available to be viewed and reviewed. This new character of art can at least allow us to feel there is endlessness in how we can appraise, appreciate, and understand performances, a kind of a “forever” that remains elusive in real life.