Rewatching our office Christmas party videos made me feel that December 2019 was another lifetime altogether. The past few months have just been too much to take in, and this is a shared sentiment by many, not just in the office, but elsewhere, in other fields. But we are hopeful, and working through it, despite the added complexities of being a self-funded museum, with no endowment, government or corporate funding to carry us through, working through a quarantine that has legally prevented us from opening since March 15. For the record, it is August 13 today; two days short of the fifth month anniversary of the COVID-19 lockdown here in Manila, reputed to be the longest in the world.

In the last quarter of 2019, we began seeing videos on various social media of how a new illness was spreading in Wuhan. It seemed frightening, but it was an ocean away. And the World Health Organization was quick to say that there was no real cause for alarm, echoing what the Chinese government was saying. Still, many felt a great trepidation, as it is common knowledge that our government has aligned itself with China, and it constantly curries favor from it by turning a blind eye on issues like contested territory, and illegal workers in the government sanctioned Philippine Overseas Gaming Operators which caters to Chinese online gambling. There were more pressing issues, like the Taal volcano erupting, sending ashes to Manila, and giving us a foretaste of the panic buying for masks that would eventually happen.

In January 20, the Philippines experienced its first brush with COVID-19. A female Chinese national flying in from China tests positive for COVID-19, and so does her male companion.1 Her companion dies, the first COVID-related death outside of China. And the government is quick to assure us that everything is under control, and that health checks are in place at the major entry ways, and yet, many of us wonder why direct flights from Wuhan to the central Philippines have not yet been stopped until almost a week after.2

A month’s lull follows, giving us a sense of security. But elsewhere, toilet paper runs out in Hongkong3 and long lines form for groceries in Singapore.4 On March 5, a man who has no travel history gets tested positive for COVID-19 as he was brought for fever and difficulty in breathing. He frequented the Greenhills Shopping Arcade, which was barely 1.9km away from Fundacion Sanso. And his wife tested positive too.5 The mall was quickly asked to close by the Mayor of San Juan to be disinfected. And we felt the fear as we saw how people avoided the place. In our tv screens, the bustling arcade that was always too full, was like a ghost town, abandoned and empty. Thinking both our staff’s safety and our social responsibility to slow down the spread, I asked our board to have a two-week lockdown, which was quickly denied.

On March 7, a Saturday, another local case was recorded in Bonifacio Global City, less than a kilometer away from where an exhibition of Betsy Westendorp de Brias was to open in the evening. Being friends with the gallery owners, I still show my support and go, as the exhibition was the focus of a newspaper article word war for two weeks running. At the opening, I feel apprehension as I see that the demographic of the exhibition was very vulnerable. Like the artist herself, they were in their 80’s and 90’s – the most at risk to COVID-19. I do not enter, afraid that I could be a carrier without knowing it. I tell myself, better safe than sorry.

On March 9, Quezon City, Marikina and Pasig record their first COVID cases. San Juan City, where Fundacion Sanso is located, called for a suspension of classes at all levels. Confused by what was happening, I call for a closure of the museum too for the day. The next day, March 10, the President called for a suspension of classes in all of Metro Manila until March 14, Sunday; but there is no work suspension yet. I ask our board for a suspension of work for two weeks, not only for the safety of the staff, but more importantly, to help slow down the spread of the disease. We understood by then that everyone is a potential vector, and that by getting out of the virus’ reach, we are slowing down its spread. We begin to see that our government was not prepared to meet this threat effectively. Rumors of panic buying start. Our request for a suspension of work, was again, denied.

We go to back to work on March 10, but in my mind, only to regroup and strategize. We once again ask our board for a suspension of work on March 11, recalling it is our civic duty as a non-essential service, to get our people off the streets and slow down the spread of the disease. We are emphatically denied. On March 13, Friday, despite the board’s refusal for a suspension of work, I release the staff’s salary early in the morning, along with some funds I have freed, to add to their personal funds. We act quickly. We put on social media that we are closing the museum until further notice and suspending our authentication services, exhibitions and educations programs, as well as our shop. I ask them to go home early, and to buy essential goods: rice, water, canned goods, medicine, batteries, and USB chargers. We prepare for a two-week lockdown, but stash away all the art into the storage. The President declares a lockdown three days after. He declared a month of emergency community quarantine, which would be remembered by many as the ECQ. We did not know that this was going to be way longer than we expected.

During the first week of the ECQ, many of our museum colleagues were still at a loss. Our small museum, used to daily catch-ups on messenger, quickly regrouped and uploaded a 360-view of the exhibition of the museum which we prepared barely three weeks earlier, to bring the museum to our audiences, who, like us, were bound at home.

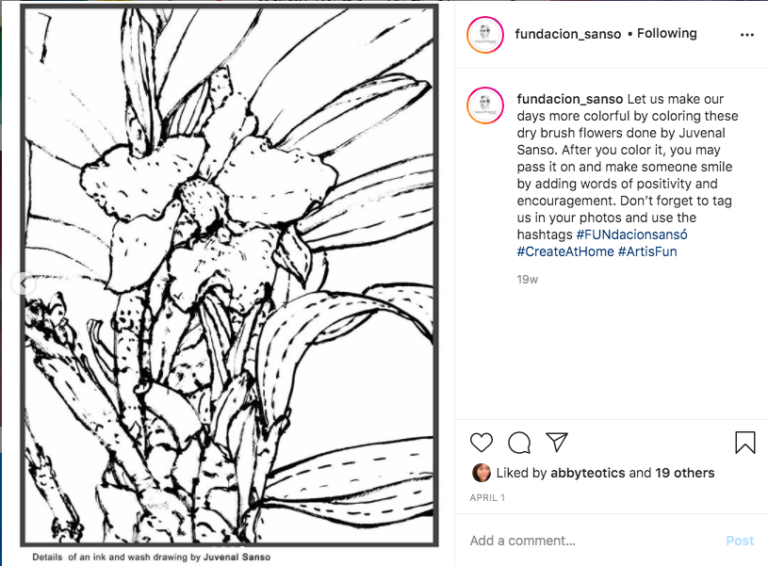

We quickly uploaded several other online content – coloring book activities for children, pdf catalogues of past exhibitions, guided photo tours, and trivia; anything we could think of to calm people’s minds as we all tried to adapt to this new situation we were all in. We also mounted a series of online talks on mental health, a subject we have latched on to last year, but became even more relevant with the ECQ.

This quarantine was so strict that no cars or people could be seen outside our street which was often busy 24-7. Secretly I worry. We did not prepare for the release of the salary for the end of the month. And our small museum normally released our compensation as cash. I also had to worry about having our cheques signed by our chairman, when no one was allowed to go out. These were among the things I had to work around with during the third and fourth week. Come salary day, I walk to do the necessary chores for the staff. Most of the banks around me were closed, and I had to figure another more efficient and safer way to do this. Thankfully, we got around these soon after, adapting new technologies and meeting with the staff every 11am on messenger, to check on their health and well-being. We also volunteer to receive pay cuts in order to prolong our resources and ensure that everyone in the museum has a bigger chance of staying employed longer.

During the second month of the quarantine, various fundraisers were being organized for the medical frontliners who were quickly running out of personal protective equipment. Some artists volunteer and I point them to Art Rocks, a viber group of collectors which was busy fundraising and was able to raise almost PhP12million within the first month of the ECQ. One of the artists tells me, “I cannot join the group because they ask for a 100% donation, and though I want to help, I also need to survive.” She eventually became my partner as we organized an independent fundraising initiative, Artists’ Pool, on Facebook and Instagram.

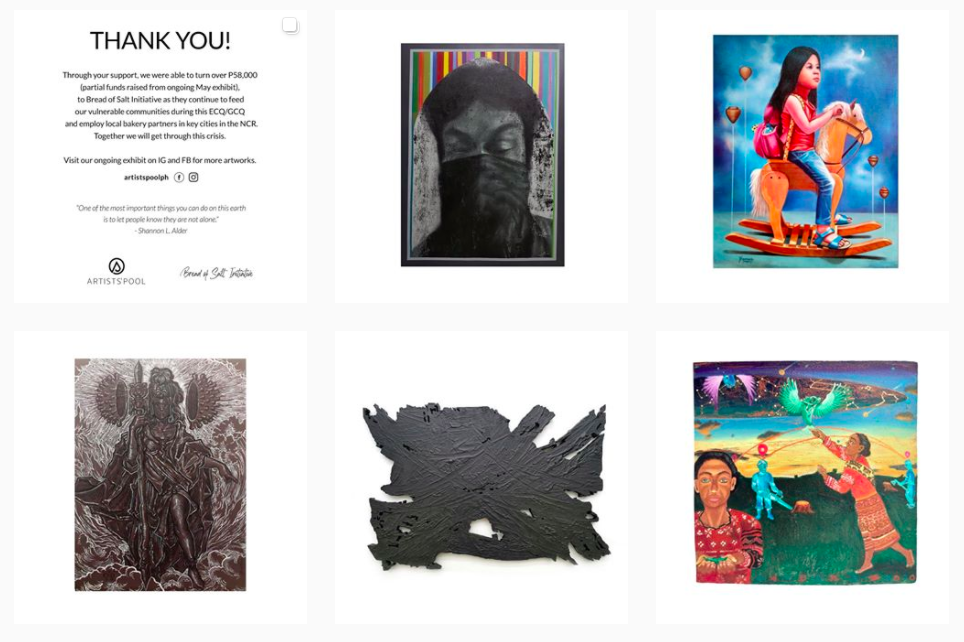

Knowing that galleries were closed, and artists had no venue to sell their works, as well as recognizing that many artists want to donate to the medical frontliners, artist Jules Ozaeta and I structure Artists’ Pool so that any artist who makes a sale, gets 60% and donates 30% to the PGH Emergency Ward team, and the remaining 10% we set aside for delivering artworks, with whatever is left behind eventually, will be divided equally among all artists who joined even if they did not make a sale. Sensing that the task of putting things to order will likely be long, and that COVID-19 will be here quite long, we make it a three-month long initiative, with one exhibition every first Monday of the month. We quickly call our friends and organize Artists Pool in 10 days.

The three months pass, and we have raised a little over P250,000 for the two charities we supported: the PGH Emergency Ward team, and Bread for Salt — an initiative which organizes local bakeries to supply pan de sal every morning to those rendered jobless by the quarantine. We were able to raise around P500,000 for the artists; with a large percentage of them young artists that were not given the chance by galleries who normally chose established artists who could command higher prices to help them cover their overhead. These new artists were eventually given space by galleries on their online platforms in the latter months of the lockdown.

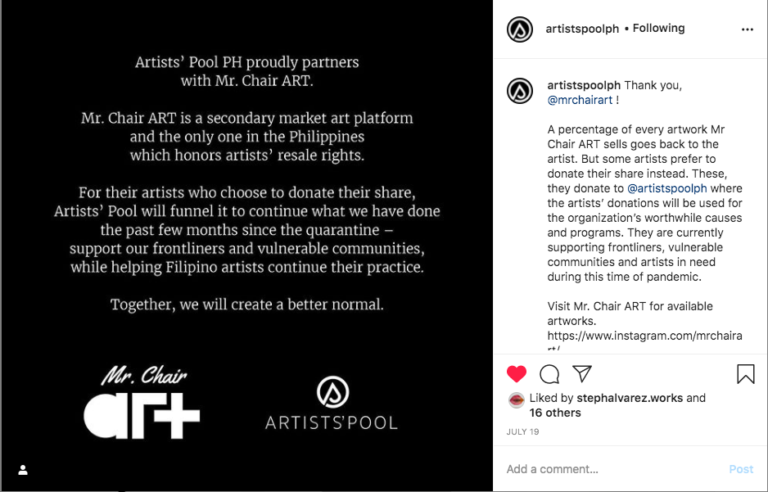

Artists’ Pool also was chosen to be the recipient of Mr. Chair Art’s artists. Mr. Chair Art deserves to be mentioned here as they are probably the only local commercial platform which honors Artists’ Resale Rights.

When the quarantine relaxed a little, we trickled into the museum to prepare for a combination of work from home and skeletal crew set ups. Closed to the public, we do our inventory, and return all the artworks that were left for authentication two months prior. We quickly get all our files to be able to work from home, and do an inventory of merchandise so that we could continue selling online. We quickly organize two online fundraising exhibitions with partner galleries and secure enough funding for museum operations and our scholarship program for several more months. We also streamline our authentication services so that we could do data gathering through email. We regroup with other museums in the community through webinars organized by various local museum associations.

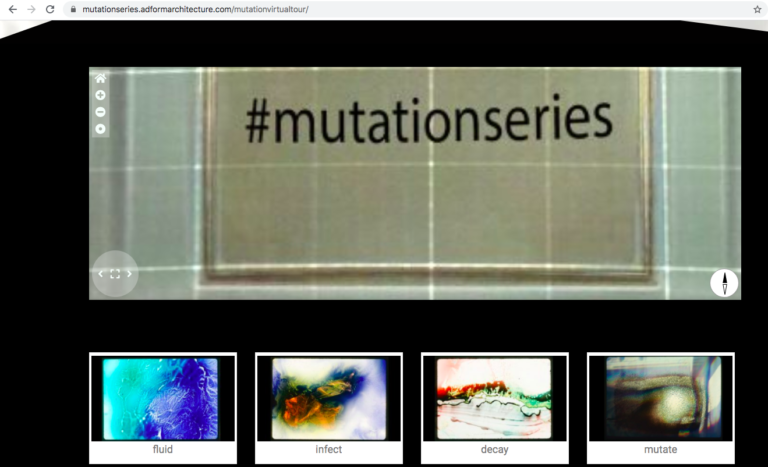

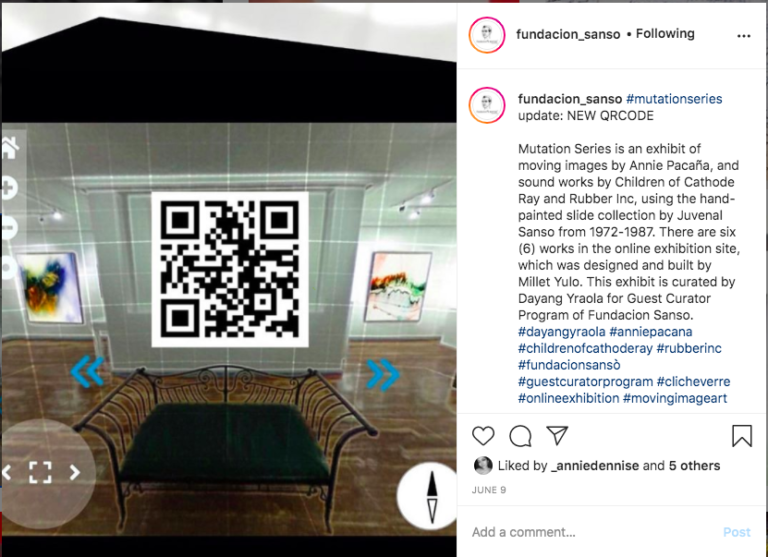

With the help of Dr. Dayang Yraola, our first curatorial grant awardee (a grant patterned after the Japan Foundation’s own curatorial development program which I was a beneficiary of years ago), we mount a very timely online exhibition called MUTATION SERIES. The exhibition utilizes Juvenal Sanso’s painted slides and is animated by Annie Pacana into a moving image with Children of Cathode Ray and Rubber, Inc creating the sound and music. The meditative virtual installation creates a platform that is appropriate not just for Sanso’s body of work, but also for the virtual nature of the exhibition, and most importantly, the need for headspace, which Dr. Yraola points as a necessity to “not be overwhelmed” by all that is happening.

Independently, I have also began working with local galleries and setting up actual exhibitions since June. Simultaneous to this though, is the greater connectivity with colleagues both here and abroad, because of both the connecting technology and the captured audiences this quarantine created. I join various talks and webinars with colleagues from Iloilo, Australia, and UAE. We talk to museum workers, to teachers, and other people who might be interested. I learn how to do an Instagram Take Over, alongside Zoom and StreamYard. And I co-organize an online exhibition about the COVID experience called Brave New World, connecting 11 galleries and over 400 local artists. We hope to publish a book soon to document local artistic responses to this pandemic.

This pandemic exposed our vulnerabilities in the visual arts field, but it also allowed us to see new opportunities. It made self-funded museums like us find our specialized niches and work on them to be sustainable. It created new ways of making a living through art, some by-passing the gallery system altogether, forcing galleries to re-evaluate their strategies and their work relations with artists. It also showed that artists can contribute in so many ways to society. It also showed that many private individuals do want to help artists in particular, in times like these. Despite these silver linings, greater safety nets must be established particularly for small institutions which need to survive through crises such as this.