Cloquet hated reality but realized it was still the only place to get a good steak.

The Condemned by Woody Allen

Art, while always an act of communication, is encountered in a variety of ways. To me, two images sum up two poles of a spectrum of encounter: the image of the lone reader immersed in a book. Opposite him is the image of the audience at a live concert: a collective immersed and united simultaneously in a unified experience. I note that the reader, while alone, is linked to others through the book. Through the book, the reader discovers that there are people who understand him, people whom he understands. Delightfully, this solitary encounter can become the basis for mingling with others who have made the same discovery. Fan clubs, concerts, conventions – these are all collective celebrations of private revelations.

The 2020 pandemic is a public and collective catastrophe that has crippled many modes of collective activity. The scale of the loss itself was a revelation to me. It wasn’t until I was forced into isolation that I realized how much art scene involves people getting in close quarters in the same physical space.

A friend has confessed to avoiding what is still sometimes called “e-numan” – ( a Filipino word – probably nearing the end of its lifespan– for communal drinking during a video conference call.), saying that the ritual worsens the feelings of isolation that it is supposed to alleviate. She experiences the e-numan as a poor substitute for a real drinking session. All the differences (leaving the house, eating food made by somebody else, physical proximity) between the two activities are experienced as a form of lack. She is crippled by nostalgia.

So on the one hand, this nostalgia is justified and unavoidable: Certain needs can only be met IRL – netspeak for “In Real Life”. As Clouquet says, reality is still the only place to get a good steak.

On the other hand, there is the telephone.

The telephone allows people to talk, but eliminates a massive amount of data that flows in real life. Gesture, facial expression, touch, smell are eliminated. You use only one of your five senses when you talk on the phone, yet the telephone is an iconic symbol of connection, an object invoked in thousands and thousands of love songs.

At the same time, the absence of the other 4 sensory channels is often experienced not as a lack but as a source of and means to comfort, so much so that people can come to prefer to have certain conversations over the phone. In fact, the addition of video has been known to induce anxiety and self-consciousness.

Perhaps the most telling example of how the telephone is treasured as a means of connection is the famed Wind Telephone, or Kaze no Denwa — a disconnected phone booth erected by Sasaki Itaru in Otsuchi, a village in Northern Japan badly hit by the tsunami of 2011. Far from being seen as a bad substitute, the telephone in the booth is seen as a kind of gift, as an object that facilitates.

Unfortunately, I seem to have written a longish parable with a rather clumsy moral. I know rituals are fusions of material and meaning. Material and meaning leave imprints in the mind and the body. My friend cannot will herself to enjoy e-numan. We don’t command our desires: we surrender to them. The places treasured rituals occupy in the ecology of our lives cannot be changed by acts of will any more than we can change our favorite food or sexual orientation by an act of will. There are rituals we have lost, rituals that likely will remain lost for a long time. It’s right and inevitable to grieve what we have lost, but the kaze no dengwa also holds out hope that new meanings can infuse the tools we now have. Rituals can also be born.

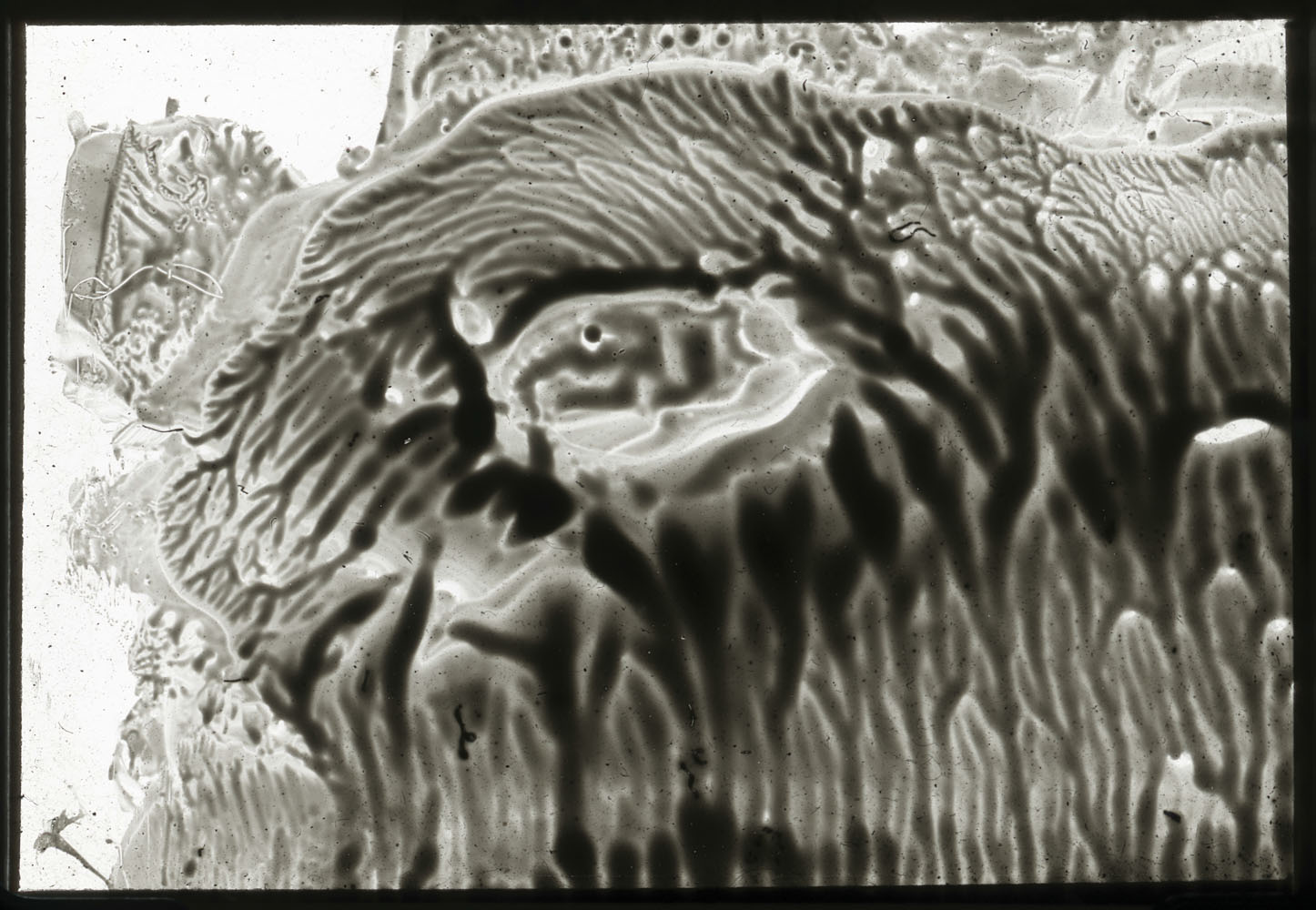

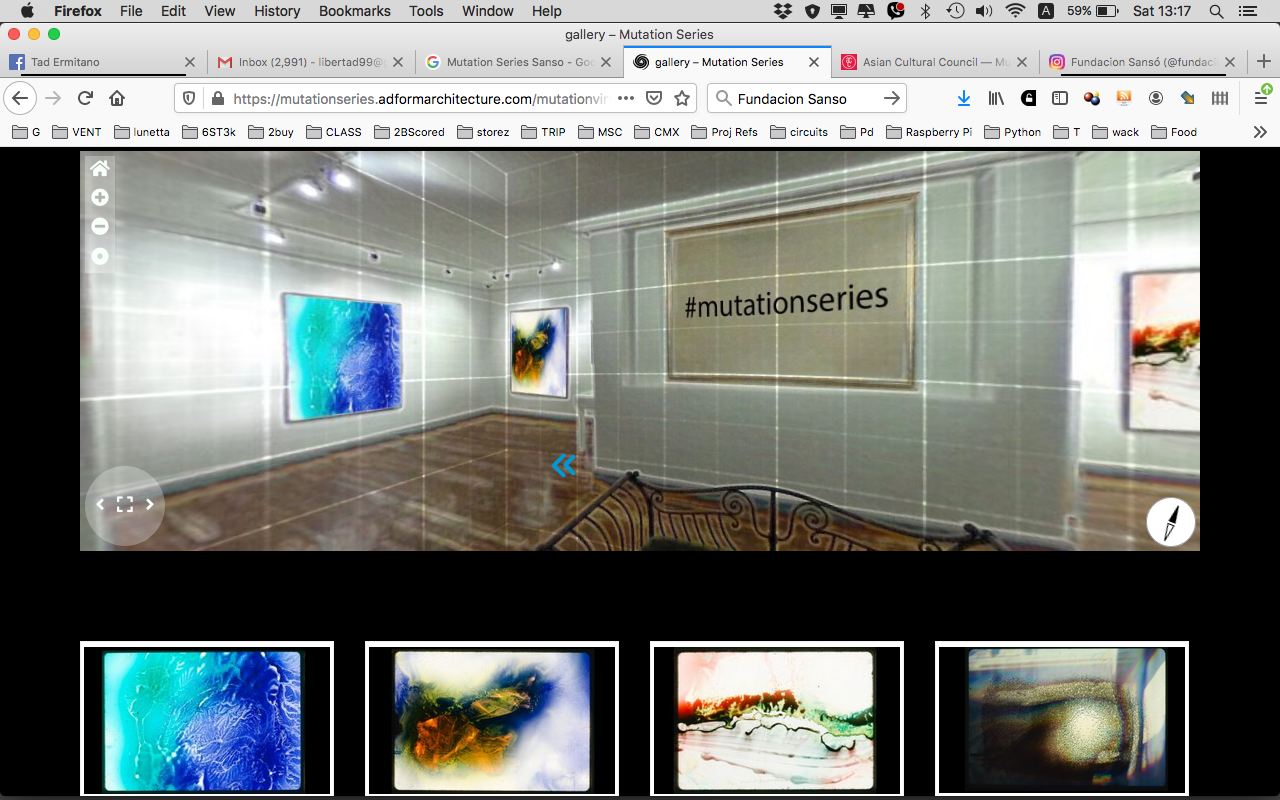

In June, I contributed music for an exhibition organized by the Gallery Sanso. The exhibition is titled Mutation Series and was curated by Dayang Yraola. The videos were edited by Annie Pacaña, who used images digitized from a collection of photographic slides created by the painter Juvenal Sanso. Sonic pieces were created by my group The Children of Cathode Ray and the electronica duo Rubber Ink, which were married to the videos that were then uploaded to the net.

We can say that two interaction forms governed the production and the encounter of the works exhibited in Mutation Series. In the case of production, the members of Cathode Ray created music together while physically and temporally distanced. As internet time lag makes it impossible* to jam music in real time over the net, each of us separately recorded improvisations to counterpoint sound files we emailed one another. This means the videos were created collaboratively and remotely. Once uploaded, the videos were then encountered in solitude, like books. This could be described in two ways: either as lonelier than watching a film in a theater — where one sees the film with an assembly – or as more relaxing than watching a film in a theater.

The twin processes of distanced collaboration and solitary encounter I described above are the oldest and easiest forms of net interaction. The same structure governs the situation of watching a movie on Netflix. I am currently involved in another project with the same structure and am sifting through a folder of sound files out of which a friend and I are meant to collaboratively shape into finished pieces for an album.

Another kind of project I participate in is the “live” broadcast. In this case, the works are encountered by a collective who are separated in space but (roughly) united together in time. This is something like listening to the radio. And like old-school radio, there is no need for the material to be performed live. I contributed a work to Sonic SONA, a net broadcast that took place at a scheduled time, and to which an assembly tuned in. In this case, the works were experienced by an audience that was separated in space but united in time. Again, this is relatively simple to do. It should be noted however, that the transmission was associated with a chatroom, which afforded the audience the opportunity to interact with each other in a way that old radio audiences did not.

We already know too well that the rituals most damaged by the pandemic are physical ones in close quarters. However, the example of the telephone points toward the potentially beneficial project of finding forms of net-mediated interaction that incorporate at least some of the characteristics that we prize in those physical rituals.

So another way of describing what the pandemic has done is to say that what has been most damaged by the pandemic are those interaction forms where the participants gather and interact in real time. The difficulties of jamming over conferencing software also illuminates the idea that there are grades and approximations of real time to aim for. It turns out that what we might call Zoom-grade real time is adequate to video conferences, but not to music jams, and so on.

Chatrooms, Multiplayer video games and Zoom offer clues and signposts towards the possibility of designing and evolving new forms of group interaction not modeled on pre-existing modes of interaction, and thus — unlike the “e-numan” that tortures my friend – less likely to strike participants like her as bad replicas of something they know and love. Most promisingly, they offer interaction where the participants, although separated in space, interact within a temporal structure closer to realtime than the forms previously mentioned.

*It would be possible to jam music where rhythm and synchronization are not critical, as is the case with certain kinds of drone music.